08 The Battle of Tar Island

“Your father is from Russia?”

“Yes.”

“Military visa?”

“Yes.”

“You volunteered?”

“My family is patriotic, Sir, I mean Ma’m.” This was mostly true. Anton’s mother, a Daughter of the Alaskan Counter-Revolution, and youngest child of a Patron, was in every way a patriot. His father had retired from the Alaskan army as an officer, but had joined it as an immigrant mercenary.

“I see.” Colonel Hoefstaedter looked at Anton’s dossier again. She said, “You’re genetically modified. Are you one of the smart ones?”

“An ancestor had something done about anemia. It was a common procedure two hundred years ago. Its all in my record.”

As the Colonel flipped through Anton’s dossier, she said, “I didn’t think cases like yours were covered by the Purity Laws”.

“They cast the net a little wider each year.”

The officer then did something that surprised Anton. She said, “I apologize for even mentioning it.

“No offense taken.”

“Let’s get down to business. You have been given a special assignment.” She paused, which he took as an invitation to respond.

“It’s an honour, Ma’m.”

“You haven’t heard your assignment yet.” The Colonel didn’t say this in a disparaging way. Whether she liked him or not, this man was a natural ally. That was more than she could say about the conscripts.

The Colonel rose from her chair, “Lieutenant, you will be briefed in full by military intelligence, but I want to talk to you personally about this assignment. You know that we’ve launched an attack along the Peace River?”

Anton nodded.

“That’s only part of our strategy. If we don’t control the factory and mine at Tar Island, just north of Fort McMurray, on the Athabasca River, controlling the Peace River does nothing for us.”

The Colonel escorted Anton to the large map of Alberta that was hanging on the wall opposite her desk. She pointed to the northern tip of the map, “Our first attack is happening right now, here.” She used a wooden pointer to describe an ellipse around a city called Fort Vermilion that was several hundred kilometres west of Lake Athabasca, on the Peace River. “That’s to protect our flank. Our second attack, the one that you will be participating in, will be here. She drew a line south-east from Yellowknife, through Lake Athabasca to Fort McMurray. “If we win both battles then we’ve secured our complete objective. If things don’t work out, our armies can reinforce each other as they retreat.”3

“Why are you telling me this?” Anton asked.

The Colonel circled back behind her desk. She used it to support what she said next. “As you probably know, the Republic’s Army, for the first time since Federation, has more conscripts than career soldiers. We’re having severe discipline problems. The General has asked me to create an informal network of trusted junior officers on whom he can count should issues arise.”

“Mutiny” Anton thought. He said, “I understand. Is that all?”

“No. There is still the matter of your assignment. Although your squadron will be part of the Second Army’s artillery corps, this will be only in a support role. We need you to survive.” The Colonel made this point as if she expected many people in the artillery corps not to survive.

“You know about the Alexandria Convention?” the Colonel asked.

Anton nodded.

She continued speaking as if he didn’t. “Normally we – the Albertans and the Republic – do not fight near Digital Age ruins. However, this battle is about one. Your platoon’s task is to occupy the control room of an ancient tar-processing factory. From the Republic’s perspective, that factory is worth an army.”

“I understand. I’ll be careful not to damage anything when I secure my objective.”

“Excellent.” The Colonel began to dismiss him, but then said, almost as an afterthought, “One more thing. I told you that you were one of a group of officers who are trusted by myself and the General. Your commanding officer is not one of them.” §

The moment Anton finished packing there was a knock on his door. He opened it to greet his commanding officer, Captain Shevetz. Shevetz’s people were from Russia too, but via a different trajectory than Anton’s father: they were political refugees and intellectuals who had emigrated to Alaska when Russia was still Communist.

Anton invited the Captain in. He assumed that Shevetz was here on platoon business, so was surprised when Shevetz began their conversation with the question, “Have you ever traveled?”

Anton looked at the man, trying to determine his point. There wasn’t much to go on. Shevetz was of medium build, had close cropped brown hair and eyes. He had a neutral demeanour that was easier to project on to than read.

Anton shrugged, “I went to Juneau once.”

“Have you traveled outside of Alaska?”

“No.”

“Not even to Yellowknife or Whitehorse?”

“No.”

“Do you have an opinion about Albertans?”

Anton replied, “Not really. I mean they’re the enemy. But I don’t think much about that. I like to focus on the positive side of patriotism, like glory and honour.”

“So you consider yourself a patriot? Don’t answer me as a subordinate, Anton. Tell me what you really think. I’m listening to you.”

Anton replied, “When I enlisted, my mother told me to be prepared to die for my country at any time. My father told me that the living are more loyal than the dead.”

Shevetz nodded his head. Anton wonder whether his commanding officer was agreeing with what he had just said, or was simply acknowledging it.

Shevetz continued speaking, “Your father was a officer, wasn’t he?”

“A Major.”

“Is he still alive?”

Anton nodded.

“He must be very loyal.”

Anton smiled. The Captain’s joke relaxed him.

Shevetz, however, was still on edge. He was impatient for this conversation to reach the destination he was directing it toward. He said, “Anton, have you ever fought before? I mean in a real battle with hand to hand combat.”

“I helped put down the Bottle-head riots.”

“What did you think when you shot your own people? Be honest.”

“I thought about the conflict between duty and patriotism.”

“Take this.” Shevetz handed Anton a small book bound in yellow burlap. Anton opened it. There was no title page and no publisher’s imprint, just text. Anton recognized the opening line, “Clients of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.”

Anton handed the book back to Shevetz. “I don’t need this. I can figure out what’s right and wrong on my own.” He spoke these words with more assurance than he felt. He wondered where his moral grounding came from. Certainly not from God and Country, like he was trained to say. No. His morality – like his patriotism – came from his family; from his mother, with blood as blue and cold as the Arctic Ocean, and his father, the mercenary.

Shevetz’s sharp voice brought him back to the present. “Lieutenant, if you worry too much about right and wrong you may forget to choose sides.”

“Captain, I also hope you survive the upcoming battle”, Anton replied.

“We can’t ask for much more than survival, given current circumstances.” Shevetz exhaled a sigh of relief. He rose to leave. At the door he hesitated, as if coming to a decision. He said, “Anton, on the morning of the battle, don’t wear your Bands.” The Officer Bands were glow-in-the-dark strips of material that allowed officers to be seen when visibility was low.

Anton noted Shevetz’s grim expression. “Thanks for the tip, Captain. Before you go, I have a question for you.”

Shevetz stiffened.

“Do you know what’s happening with the First Army? The last I heard they were stuck on the Slave River portage. Have they made it to Peace River yet? Have they begun the assault on Fort Vermilion?” I was a practical question. If the First Army had already failed their mission was doomed. But the question itself based based on information enlisted men did not have. He could see that Shevetz knew something, but Shevetz viewed the question as a trap. He started to say something, stopped, nodded his head glumly, and then took his leave without saying another word. Anton saluted his back. §

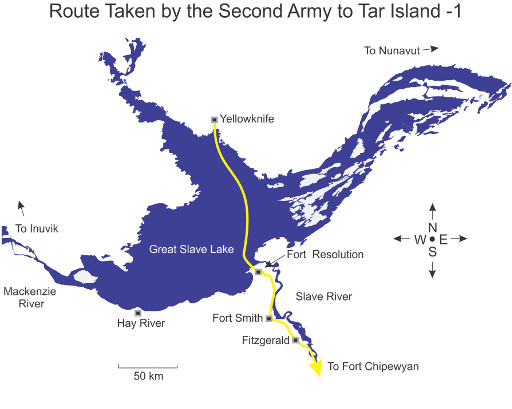

The Second Army mustered at Yellowknife because of its central location between Nunavut and Alaska. A ramshackle flotilla of boats ferried the Army across Great Slave Lake to Fort Resolution, a small tourist and industrial hub situated immediately west of the mouth of the Slave River, 500 kilometres north of their ultimate destination.

The ferrying across Great Slave Lake took the better part of two days, with the biggest delay coming from the horse barges, which could only travel when the lake was calm. The infantry spent one evening at Fort Resolution. The next morning they began a quick march south along the western shore of the Slave River. Although the population of the region was in decline, the farms that remained were prosperous enough to maintain the roads year round. The cavalry traveled by barge down the Slave River.

The cavalry met the infantry at Fort Smith, where the river barges had to empty because a series of four rapids rendered the Slave River unnavigable for the next 25 kilometers. The portage had been difficult for the First Army, which had passed through here four weeks earlier. The ground was scarred by the marks made by wooden skids. At Cassette Rapids they saw their first dead slaves, poor souls who had been left for compost on the cold, rocky ground.

The portage ended at the town of Fitzgerald where the entire army got onto barges and floated down the Slave River to Fort Chipewyan, on Lake Athabasca. Fort Chipewyan, surrounded by rivers, marshes and lakes, had never been a fully integrated part of Alberta. Its physical separation from the south was compounded by centuries of anger at how the Athabasca River, and the entire Lake, had been poisoned by the upstream mines. The Fort surrendered to the Second Army without a fight.

At this time of year, the arctic was much easier to reach than leave via Fort Chipewyan. The problem was that the western edge of Lake Athabasca was impassable except in winter; the Second Army had arrived in spring, after the thaw. The entire region was a marsh. With the persistence of men who have no authority but to follow orders or die, the soldiers began the tedious task of ferrying men, horses and ordnance south in barges, through the delta to hard ground 50 kilometres south of the Lake. The first convoy took 5 days to transport a fraction of the Second Army.

They were saved from a several month delay by a cold spell that made the winter road through the marsh suddenly navigable. Thanks to the freeze, the entire Army, save for a few slaves, cannons and horses, made it to the head of Highway 63 in one brutal, 36 hour march. From there it was a straight shot to the factory at Tar Island.

The pace was set at 20 kilometres a day, which for an individual soldier walking with a heavy pack through rough terrain was reasonable. For an army with cannons and skittish horses, it was extreme. Nevertheless, the demoralized soldiers kept to the pace: endless delays had made everyone anxious to move.

After less than a week they arrived at the tip of the North Pit, at the point where Lake McLellan, Highway 63 and the Athabasca River meet. They were one day’s march from the front.

Camping was arranged on an first come basis, except for the best spots, around Lake McLellan, which were reserved for the nobility and their horses. By the time Anton’s squadron arrived, the camp ground had spread out around the northern-eastern tip of the mine.

Because of the way the senior officers talked about the Tar Island mine, Anton had envisioned it to be like a flowering, stone garden. The terraced, muddy brown-grey North Pit might once have been an Eden for machines, but never one for humans.

The ground was wrinkled, sharp and hard. It had rained recently. There were dark pools everywhere that looked more like oil than water. Anton imagined that if he lit a match the landscape would burn like brimstone.

While they were setting up camp Anton stumbled upon the remains of a team of slaves who had died trying to remove a cannon from where it had become stuck in a crevice of bitumen. The weight of the weapon had caused a piece of rock to crack. This created a small landslide, which had half-buried the cannon. The slaves had no gloves, so their hands were scarred and bloody. They had been shot in disgust, or despair, by an owner who couldn’t collect on his contract to deliver the gun to the front. After camp was set up, Anton’s men removed the corpses from under the ruined cannon, and buried them in gravel.

The North Pit was a cemetery for machines from the Digital Age. It contained giant backhoes, pile drivers and trucks. A few were decrepit, but a surprising number were not. Their camp clustered around the edges of a 10 metre high dump truck, at the top of a switchback road. When the truck had broken, two centuries ago, it had held 400 tons of rock. Over time, most of the rock had fallen out through rust-holes, causing the truck to bury itself. Although it was a good site for camping because it was well-drained, flat and sheltered, it was a poor choice for the soldiers because the skeleton machine haunted their dreams. It was like sleeping on Grendel’s lap. §

The next day the Second Army began the last leg of its march, serenaded by the loudly cawing birds that nested on the walls of the mine.

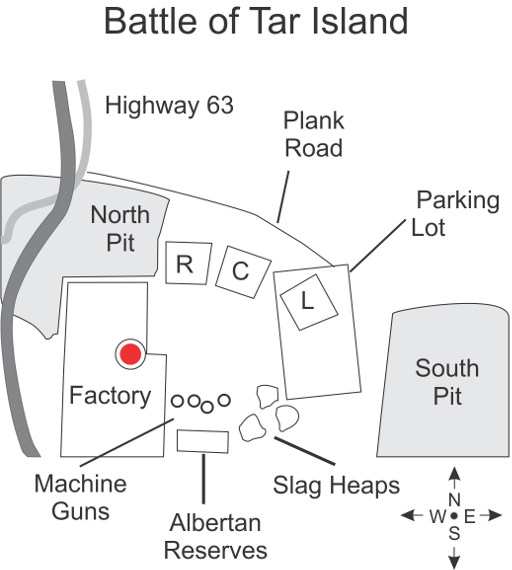

Just south of Fort MacKay, on the northern edge of the Alaskan trenches, there was a bottleneck created by a plank road that had been placed directly in the path of the Second Army. Passage over the road was blocked by Alaskan MPs with drawn guns.

At first Anton could not determine why the plank road was there at all. Then he heard the clatter of hooves on wood. Slaves had built the road so that the Alaskan horsemen could reach their position on the Army’s left flank without having to risk crossing the hard, rocky ground.4

Although the plank road was barely 2 kilometres long, the progress of the cavalry from Highway 63 to its destination – the parking lot that traced the eastern perimeter of the factory – was slow. Every few minutes a horse would stumble and fall off the road. Most of those that did broke limbs and had to be killed.

The crowd of soldiers in the front end of the bottleneck became angry as they became more compressed. Conscripts started to heckle the cavalry. Phrases like “look at the pretty officers” flew through the air. The officers mostly ignored the jibes: they were too concerned about the safety of their mounts. It was the military police who took issue with the hooliganism.

Initially the MP presence was slight, perhaps one policeman every twenty metres. After an hour the entire length of the plank road was lined with police. They lowered their face masks. A few cocked their guns. Most were holding truncheons in their dominant hands, facing the crowd, waiting to be attacked or to attack.

One rowdy conscript fired his pistol into the air. A squadron of military police immediately pushed out into the crowd. The first to arrive shot the conscript. While this was happening the crowd unsuccessfully tried to edge away from the military police.

Once all of the cavalry had reached the parking lot, a checkpoint was opened in the plank road. All of the infantry slowly funneled through this narrow gap. The identity of each soldier was checked against a list.

It was dusk by the time Anton made it to the other side of the plank road. He was herded past the slave quarters to the portion of campground reserved for Shevetz’s Company.

Once his tent was set up, Anton left his men under the guard of his Platoon Sergeant, an Inuit from the eastern arctic who had the unlikely name McAllister. He set off for the trenches to see if his gun had arrived.

The trenches were numbered with an alphanumeric system. Anton followed a radial trench numbered 3 to where it intersected with row c. He found his gun in position, exactly as planned. He identified it as his by the crack on its muzzle.

A full moon had risen in the south-east, so Anton could see the battlefield clearly. His primary objective, the factory, was to his right – the south-west. The factory’s northern tip was behind Alaskan lines. That was very good news. The bad news was the row of machine gun towers to the south. They were close enough that Anton could see the face of the Albertan who manned the tower due south of him. The Albertan waved. He was wearing the Albertan version of the Bands, so looked like a glow-in-the-dark skeleton when he did so. Anton flashed the Albertan a peace sign with his right hand. The Albertan gave him a thumbs up.

To the east of the the Albertan machine guns was a field of barbed wire that ended in three slag heaps. Beyond the slag heaps, just north of the South Pit, was the parking lot where the Alaskan cavalry was camping. The cavalry camp looked like something out of Camelot. The officers had grand, striped tents. Even the horses had colourful temporary stables . The flickering light of hundreds of torches added to the sense of medieval pageantry.

The spectacle disturbed him as much as did the thin, utilitarian machine gun towers.

Anton crawled through the trenches back to the camp in a sombre mood. When he reached the point where the trenches and campground met a voice whispered out of the darkness, “My friend, what are you doing wearing your Bands? Do you want to get shot?” Anton looked for the source of the voice but couldn’t locate it in the blackness. He acknowledged the comment by waving his right hand in the approximate direction from which the voice had come, and then quickly slipped away to the privacy, and security, of his tent.

It started to rain.

For most of the night the rain fell as mist. §

The next day began with a court martial. A Sergeant had allowed the men he commanded to desert. They had escaped into the North Pit. The Sergeant’s trial was brief, just a bland recitation of the facts, and a sentence. The only part of the event that was contentious was the manner of execution, which was debated in loud, but unclear, voices by the court’s two presiding officers. In the end, the defendant was shot in the pen where slaves were flogged.

Anton planned to spend the day exploring the factory. Just after noon, he was informed that he had permission to do so. He left his men under the guard of one of the Colonel’s men – a noble from Fairbanks.

The two military policemen who guarded the entrance to the factory expected him, but he was not allowed to proceed with his inspection without an armed guard. After an hour’s wait, a large, affable looking Private presented himself. When Anton asked what had taken so long, the Private replied that the military police were stretched thin this morning.

They entered the factory. It was silent and empty.

“Have you seen any Albertans in here?” Anton asked the guard.

The guard was walking two paces behind Anton. He stepped one pace closer so he could converse more easily. He replied, “No, Sir. Albertans are very strict about the Alexandria Convention.”

“Where are you from?”

“Tuktoyaktuk.”

“There are a lot of Russians there.”

“Yes, Sir. My great grandmother sailed across the Arctic Ocean, from Archangel.”

“My father migrated to Alaska from Vladivostok.” That broke the ice.

The MP continued,“If you don’t mind my asking, Sir, you’re an engineer, correct?”

“Yes.”

“Why are you also commanding an artillery platoon? It seems the brass don’t know what to do with you.”

“Colonel Hofstaedter wants veterans like me to firm up the ranks.”

“I see.”

They were standing at the north-eastern corner of the factory. Anton took out his map. He attempted to compare it with his surroundings. He couldn’t.

The Private stepped beside Anton, to help. Anton handed the map to him, and took one step backward.

The MP looked at the map, at the factory, and then shook his head. “Wrong map?”

“Not exactly. The problem is that there is no orientation or scale information. This

map portrays one of the factory’s corners, but we don’t know which one.”

“We should go to that corner, Sir.” The guard, without hesitation, pointed to the south-east. “Its safer there – closer to our lines.”

Anton nodded. Near and safe were good starting points for a random search.

The first corner they reached didn’t match the map either, but they saw that 500 metres away there was a second corner, created by a narrowing of the factory, that did. His objective, the control room, was perched on a metal tower that could be accessed by two metal catwalks and a half-dozen service ladders.

“We’re going to that tower to look around.” Anton spoke the words like a command.

The Private looked at his watch. “Certainly, Sir. We have one more hour, then they’ll come looking for us with the dogs.”

They entered the control room via a door on its northern wall. The eastern wall of the room was dominated by a window. The western wall was lined with three large panels, each of which displayed an electronic map of one of the factory’s main levels. A fourth panel displayed a schematic map of the entire factory. Anton inspected the schematic map. Green lights indicated functioning nodes, red those that weren’t. The perimeter of the map was ringed with red lights. What amazed him was the abundance of green lights. These showed that the entire south-western quadrant of the factory – the part behind Albertan lines – was functional.

Anton realized that the Albertans were fixing the factory. It was a humbling thought. This vast enterprise was one of the pinnacles of human technology. It had employed the largest machines, it had used the most energy, it had impacted the most things, including the climate of the planet itself. The Albertans were about to make all this work again; the Republic thought it could defeat them with horses and sabers.

The Private said, “Its time to go, Sir. We really don’t want to deal with the dogs.”

“I’m on my way.”

Anton turned his back on the digital maps and briskly exited the factory. The MP easily kept up with Anton’s pace. They returned to the Alaskan lines in silence, except for the sounds their hobnailed boots made on the ancient concrete floor.

Anton was relieved to discover that no one in his platoon had deserted.

§

By 22:00 all activity in the right and centre flanks had ceased. The noise from the pavilions on the left flank continued until after midnight, when the cavalry officers ran out of wine. The camp remained silent for perhaps thirty minutes. At approximately 1 a.m. soldiers on the Alaskan right flank started to sing. No one voice was loud, but the volume increased as more and more soldiers joined in. The singing sounded beautiful in the pitch dark, but there was nothing particularly beautiful about it: the soldiers’ voices were rough and desperate.

They sang,

Arise ye clients from your slumbers

Arise ye prisoners of want

For reason in revolt now thunders

And once again ends the age of cant.

Away with all your superstitions

Servile clients arise, arise

We’ll change henceforth the old tradition

And spurn the dust to win the prize.

So everyone, come rally

And the last fight let us face

Let us occupy our world,

And unite the human race.

A chorus of cheers rang out from the Albertan lines. While the Albertans cheered a dozen gun shots were fired in rapid succession. Someone behind the Alaskan lines shouted “its all right, he got carried away”. The singing stopped; the camp became quiet again.

Anton was dreaming deeply when he was woken up by the Private who had the dawn watch.

Even though it was twilight dark, about a quarter of the camp was up. There were shadows of people everywhere, limned by the light of the campfires. Remembering the warning he had been given by Shevetz, Anton looked for glowing Officer Bands. There were some away to the east, but none nearby.

While he was cleaning up from breakfast he saw the glow of a Band, but at an odd angle. It came from the tent of the nobleman who had guarded his troops yesterday. A moment later the man’s corpse passed by on a stretcher. Anton made a point of not noticing.

It was 6:55. According to the attack plan everyone was to be in position at 7:29, 60 minutes after dawn, and 31 minutes before the battle was scheduled to begin. He signaled for his men to get in position, counting them as they went.

The platoon was in place with minutes to spare.

Anton counted his men again.

At 7:30 all of the campfires in the right flank were put out simultaneously. The entire Right Flank became enveloped in smoke.

“So what are we going to do, Lieutenant?” Anton could not see who had spoken, but he knew who had: a conscript named Atlutaq, who was one of a pair of brothers from the North Slope, near Prudhoe Bay.

Anton replied, “Stay alive.”

Atlutaq’s brother Tulimaq, who Anton also could not see, laughed, “That’s a good plan.”

“How are we going to stay alive?” This question came from Atlutaq.

Anton knew that his men were going to surrender whether he did or not. He said, “For starters, don’t fire that gun.” He nodded toward the cannon even though it was enshrouded in smoke. “Its more likely to kill us than the Albertans.” His words were met with a chorus of agreement.

“Then what?” This question came from his left, behind a pile of sandbags. It was the GM from California. The one who never spoke.

Anton inhaled deeply before replying, “I think its safest to take our objective. The Albertans have abandoned the factory.”

There was a long, tense pause.

Atlutaq broke the silence, “You’ve got to be fucking kidding.” Anton lowered himself completely into his trench, and removed his revolver from its holster.

A muffled voice from behind Anton said, “I agree with Atlutaq. There’s no way I’m going past another MP checkpoint.” That was McAllister. He continued, “Lieutenant, you’re OK if we surrender? That’s what all of Shevetz’s men are going to do.”

A gun fired nearby.

Anton said, “Surrender. There’s no sense in dying needlessly. We don’t stand a chance against the Albertan machine guns.”

Tulimaq said, “You’re a good man, Lieutenant. I’m glad I didn’t have to kill you.” The Tlingit Private emerged from the smoke centimetres from Anton’s face, patted him once on the back, and then crawled around a pile of sandbags to join his brother.

When the smoke cleared Anton saw that he was completely alone. The entire platoon was hidden from him behind sandbags.

An engine backfired. Anton looked through a crack in the sandbags. Six 400 ton dump trucks had entered no-man’s land from the Albertan side, and were driving directly toward the Alaskan right flank. The trucks were filled with enough slag to bury a city block. They drove to the edge of the Alaskan trenches, and then stopped. They cast the entire Alaskan right flank into shadow.

When the Albertans trucks began their advance, a group of Alaskan military policemen rushed toward the right flank. One officer, a Second Lieutenant, was shouting for the artillery to begin firing, and for the infantry to prepare for attack.

The right flank did not attack. A few started to sing the song from last night.

So people, come rally

And the last fight let us face

Let us occupy our world,

And unite the human race.

The military police were uncertain what to do. It was one thing to shoot a random soldier who had gotten out out of line, quite another to start shooting when one third of the army was mutinying moments before battle.

The attack whistle sounded.

The first charge by the Alaskan cavalry was repulsed by the Albertan machine guns – there were dozens of dead horses and men. The cavaliers who remained regrouped for another attack. The centre held: it was not in outright mutiny – many riflemen were providing covering fire for the cavalry – but no one was advancing toward the Albertan machine guns.

On the right flank soldiers, in ones and twos, were crawling toward the Albertan lines while waving white flags in the air. Others had taken cover behind the Alaskan trucks, and were having a fire fight with their own MPs.

The truck nearest to Anton’s platoon blasted a loud note on its horn, and began to back up. The driver in the cab signaled frantically for the surrendering Alaskans to retreat with him. While his men set off toward the Albertan lines, Anton crawled in a perpendicular direction, toward the factory.

The MPs who were guarding the entrance to the factory had been shot and their gear destroyed. Anton paused to look at the dead soldiers. He was glad to see that none of them was the Private he met yesterday.

“Drop your weapon and put your hands behind your head.” A military policeman had sneaked up on Anton from behind.

“What are you doing here?” the MP shouted.

“I’m here to secure the room that controls this factory. Its one kilometre south, where the factory narrows.” He indicated the direction with his left elbow.

“Just you?”

“I’m supposed to be here with two squadrons. My men were killed by the Albertan machine guns. My name is certainly on your list. I’m First Lieutenant Anton Rostov. Didn’t you see me here yesterday?”

“There is a list, but I don’t have it. My orders are to shoot deserters on sight.”

“I’m not a deserter.”

“You’re an officer. Why aren’t you wearing your Bands?”

“Enemy snipers are targeting the Bands. Just before battle began I was ordered to take them off because we’d lost too many officers.”

“That would never happen. And if it did, why did your men get hit and not you?”

“I wasn’t hit because I took my Bands off.”

There was the sharp report of rifle fire; the MP fell to the ground, dead. Anton waved in the direction from where the shots came and mouthed the word “Thanks”. He grabbed a revolver from the holster of the dead MP, and slid down into the gutter that paralleled corridor he’d just been walking along. He lay still until his beating heart had slowed down.

Once his heart had stabilized and his eyes had adjusted to the darkness, he began crawling slowly forward to his destination. He was underneath a column of four large articulated pipes. They traced the eastern edge of the factory.

After crawling south for one kilometre, he reached an access ladder that led to one of the catwalks radiating out from the control room. After minutes of careful listening he rolled out of the gutter, leaped onto the ladder, and quickly raced up. Climbing took no great effort, but coping with the fear of being shot did. Once he’d made it to the top he lay flat on the the metal slats of the catwalk, gasping for breath.

The control room was only metres away. Anton pulled himself up to a crouching position, and then stood up slowly. To keep his movements quiet, he focused on being balanced. He silently entered the control room through the same entrance he’d used yesterday.

He had secured his objective. §

Anton walked over to the window, curious to see how the battle was progressing. The Alaskan centre and left flank were mustering for what looked like a final attack. The right flank had completely mutinied, although many died before they succeeded in reaching Albertan lines.

Even though their numbers had been greatly reduced through desertion and machine gun fire, the Republic’s troops still outnumbered the Albertans. The Alaskans had one tactic, the same one they had been trying all day, which was to attack the Albertan machine guns from all sides at once. The machine guns could fire hundreds of rounds a minute, but could only cover a few degrees of the field at one time. If they were rushed from all sides they could be taken.

Before the last charge began, a handsome cavalry Captain called his men around him and took out a book. Through his field glasses Anton could see that the Captain was quoting from a collection of Tennyson’s poems. Whatever poem it was that the Captain read, it roused the horsemen, who clashed their sabers together in solidarity. The horsemen turned toward their enemy. The attack was sounded. The soldiers on the centre tentatively crawled toward the Albertan line, while the cavalry rushed forward on the left.

The Albertan machine guns fired only on the cavalry. The infantry could have won the day. But they held back. When it became clear that almost the entire left flank – the flower of the aristocracy – was dead, the centre surrendered en masse.

A flash of light drew Anton’s gaze away from the battlefield to a point immediately below the control tower. The ground here was untouched by battle except for one lone Alaskan cavalry officer who lay dead under his horse. The soldier and his mount were close enough that Anton could see them clearly, without the assistance of field glasses. The officer had broad, sweeping mustaches, and a metal hat plumed with white horse hair.

The dead officer reminded Anton of one of his father’s treasures, an ivory engraving of a distant ancestor who had fought with the Russian cavalry against Napoleon. The engraving was carefully stored in a dainty woman’s locket. The ancestor had died at the Battle of Borodino. When he did, he must have looked much like this, a flamboyant horseman ripped to pieces by artillery.

“Ahem.”

The intruder, an Albertan Sergeant, cleared her voice a second time to ensure she had Anton’s attention.

Anton knew what to do next. He said, “Let me put my pistol onto the ground before I raise my hands”.

The Sergeant replied, “There is no need to raise your hands, just put down all of your weapons. The war is over.” Fin