Protected: My Last Adventure

06 Social Networks

“Gawd I love them fat!”

Keelut looked at his colleague: he was one millimetre of cotton away from penetrating the dancer who was sitting on his lap. The folds of fat on the dancer’s legs and stomach made her look – given the context – like a rutting elephant seal. Keelut glanced at the bouncer to see if there was going to be any trouble.

Without intending to, Keelut caught the hopeful smile of a dancer. She had long, sandy blond hair which was braided in the Russian style. With her pert butt and slender frame, she was by no means a conventional beauty. But her fair skin was unblemished and she had all of her teeth. Keelut found her attractive.

When the dancer noticed Keelut looking at her, she smiled brightly. After a moment, she looked away. If she was trying to be coquettish she failed. She had the manner of someone who had been picked on but whose spirit had never broken. The dancer’s vulnerability made her less attractive to Keelut. But at the same time he liked its compliment: persistence.

The dancer caught his eye again. Keelut decided to meet her. He approached her indirectly, by walking along the perimeter of the room, rather than trying to wend his way through the maze of small tables that lay on the direct path between him and her. He paused to examine the dancer when he got to within two steps of her. She was wearing a ragged dress and hand-woven sandals. The castaway look had been in fashion since that play about Long Beach Island. The style struck him as impractical, particularly in wintertime, but there was no question that in this context it worked.

The dancer said, “Sit here.” She grabbed the strap of his sabertache and lightly tugged, encouraging him to sit down. He did not sit down. She let her hand fall into her lap. He gestured for her to accompany him to the Patron’s Lounge. She nodded assent, and smiled to herself. He extended an arm to help her stand up.

Keelut walked slightly ahead of the dancer, hoping that no one from work noticed with whom he was leaving and to where they were going. It was one thing to be seen in the company of a high-priced Inuit courtesan, and quite another to be seen with a skinny, low class WASP. The Director of the Institute where he worked was very conservative; it was best that there be no gossip.

The entrance to the Patron’s Lounge was discrete but well guarded. If there had been doubt about Keelut’s rank he would have been asked for his papers. He possessed enough trappings of nobility – a saber, a school tie and an expensive suit – that he was allowed to enter the Lounge unchallenged. The moment he did so he slowed his pace to allow the dancer to catch up to him. When she did, he clasped her left hand with his right. He led her to a semicircular couch beside an unused, small stage.

Keelut spoke first, “What’s your name?”

“Tanya Anderson.”

“That doesn’t sound like a stripper name.”

“It isn’t, its my real name.”

“Are you any relation? I mean, to the Andersons.” He was making small talk; he was certain she was a nobody.

“Yeah. My great-grandfather is the Anderson.”

“You mean the head of the Merchant House?”

She nodded her head twice.

Her claim to noble status puzzled him. The Anderson’s had inter-bred with Tlingit, Unanga and Yupik, so were mostly broad shouldered, dark haired and swarthy. This dancer had light hair, grey-green eyes and a slight frame. Were her low-class features recessive traits? Was she genetically engineered? Looks were only part of the mystery. The bigger question was why, if noble, was she here at all? She must have been shunned

Keeluk said, “I’m an Okpik. I’m surprised we haven’t met before. My family goes to all of the Anderson balls.”

“Mine doesn’t.” She spoke these words not to him, but to his sword, an emblem of status, which he had layed carefully on the couch beside them.

The knowledge that she was of higher rank than he was – although shunned by her family – left things in an indeterminate state.

“Why did you take me to the Patron’s Lounge?” Tanya asked.

Keelut put his left hand on her thigh. She stiffened. After a moment she relaxed slightly, but remained tense. He looked at her, trying to capture the feeling of power he usually felt when alone with a dancer. She didn’t look away.

He picked up his drink as if that was the reason his hand was retreating from her thigh. “Where are you from?” he asked.

“I was born in Barrow, but I grew up in Fairbanks. I’ve been living in Inuvik for the last 5 years”, the dancer replied.

“Army brat?”, he asked.

Tanya looked at Keelut’s sword and nodded.

“Where do your parents live?” he asked.

“Mom’s in Yellowknife”, she replied.

“What about your father?”

“He’s just been deployed to Peace River. At least that’s what we’ve been told.”

“Poor man”. Keelut spoke without thinking. He had heard rumours of the terrible slaughter that was happening on the southern front. There was a moment of embarrassed silence. He looked around the empty Lounge wondering what to say next. When he looked back at Tanya he saw that she was looking at him full on. It was only he who was embarrassed. His faux pas, if anything, had made her more self-assured.

“What do you think of the undeclared war with Alberta?” she asked.

Her emphasis on the word ‘undeclared’ revealed her political leaning: she was a pacifist. Fair enough. Only aristocrats wanted this war, though right now she and he were not so far apart in their views. Even the high born were being drafted now. Not that he really feared the draft – he was a scientist, he would never see the front. Keelut’s view of the war was materialistic. He thought of the broken machinery that surrounded him in his lab at the Institute: all sorts amazing devices that no longer worked because Alaska had no access to certain strategic materials. “I think defeating Alberta is the Republic’s only chance. We need their technology and resources.”

Tanya smiled ruefully, “That’s exactly why we’re loosing.” She spoke these words so definitively the conversation ended.

When the next song began she gave him a lap dance, which was perfunctory not so much because she was going through the motions but because the uncertainty between them persisted. He was more respectful than most of her clients and he thought her as attractive as any of his peers, but they were separated by class and ethnicity.

Tanya began a second dance. Keelut gestured for her to stop. She sat down beside him. In an attempt to strike up conversation she said, “Did you know there are no Patron’s Lounges in Alberta?”

He nodded affirmatively as he replied, “Alberta is a different world. Discrimination on the basis of rank is illegal. There are no Patrons, at all.”

“What do you think of that, as a man whose rank lets him wear a sword?” , she asked. He saw the hint of a smile in her eyes. He did not rise to her bait. Because of his work, he thought long and seriously about this topic. He said, “I think class distinctions are holding the Republic back.”

These words were easy to say, and Keelut mostly believed them, but he knew full well that it was easier to talk about change than implement it. The Table of Ranks favoured him both at work and here in the Patron’s Lounge. He looked at the dancer dispassionately. Because he was a noble and she was shunned, he could do anything to her, up to and including rape, and get away with it provided he didn’t cause her to bleed, or die. He thought of once again putting his hand onto her inner thigh, at the point where her ragged dress broke into two triangular folds of material and then … Tanya was watching him intently. Keelut placed his hands on his lap, and then shuffled in his seat. Tanya smiled with relief.

“Where do you work?” she asked.

“At the Fort. I’m a computer programmer with the Ministry of Information.”

“I didn’t know there were any computers left to program.”

“I’m working on one that was found at the Burnaby dig. Have you heard about it?”

“I know about the dig. I study archeology at the University. But nothing first-hand. Have you found anything interesting?”

“A few things. We only booted the computer up for the first time today That’s why my team is here celebrating.”

“What do you expect to find?”

“Poems. Military secrets. That sort of thing.”

“Poems. Seriously?”

He nodded. “There are a bunch of poems by Shakespeare, Yeats and Keats that we know exist but have been lost. The computer contains a database …”

“What kind?”

“Its a social networking site.” She gave him an uncomprehending look so he qualified, “Its a dating service – a kind of electronic bulletin board where unmarried adults posted profiles, and sent each other messages.”

“People used to court using bulletin boards on computers?”

He nodded. “There was no privacy in the Digital Age. It was all right out there for millions to see.”

“But they did send each other poems, just like we do now?” she asked hopefully, distressed at the crassness of 21st century manners.

He nodded, “Exactly. We’ve already found a half-dozen fragments.”

“Can you recite one?”

“I can.” That afternoon he’d spent so much time analyzing one verse he’d memorized it.

The distance between them had narrowed enough that he did not feel intrusive when he carefully placed his hand on her left thigh, just above her knee, far below the jagged hemline of her dress. She did not flinch.

Instead she cupped his hand in hers.

He recited the fragment with a voice that was so quiet it was almost a whisper,

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

Keelut had closed his eyes when quoting. When he opened them he realized that Tanya looked beautiful in the red-yellow glow of the flickering candlelight.

The moment had stretched into a minute when they were interrupted by a bouncer, who said something to Tanya. The bouncer left and Tanya spoke, “Keelut, I’m next on the main stage. Are you going to wait for me?” Her voice was tentative, not craven. She wasn’t pushing her product, she was asking.

He looked at his watch. He was already late: his rooming house had a 10:00 p.m. curfew. He shook his head, no. She frowned in an exaggerated way.

He said, “If I find any more good poetry fragments you’ll be the first to know.”

“That would be grand.” She smiled. She chastely held his hand in hers. This intimate gesture was not part of her act.

As Keelut paid Tanya he deliberated about asking for her card. He wanted to call on her and ask her out in a proper way, but a ranked society is full of constraints: noble men rented strippers, they did not date them. He could not get past that. So instead of asking for her calling card, he placed one of his into the middle of the wad of money with which he paid her. She enumerated the bills carefully but gave no indication she noticed his card. She pecked him on the cheek, thanked him for reciting the beautiful poem, and was gone.

§

“Jason, what’s up with the shit-eating grin?” Keelut asked. It was an effort for Keelut to sound jocular.

“My 8-bit chip worked”, Jason replied.

“The one you’ve been whittling in Hangar 3?”

“Don’t be such an ass. And don’t talk to me like that. I’m your boss now.”

Although Jason’s promotion annoyed Keelut, what really bothered him was the work Jason did to get that promotion. Keelut said as caustically as he could, “Jason, did it ever occur to you that poplar wood is not an appropriate material for a central processing unit?”

“You know full well that if Alaska had a better technological base we’d be doing my project differently.”

“What are you two gentlemen talking about?” The Director had arrived without either of them noticing. Today, as on all days, he wore a finely woven, blue woolen suit, a starched white shirt, shiny dark leather shoes, and a tie from the Crescent school.

Keelut spoke pre-emptively, “Jason was bragging about how his 8-bit chip is working without using any electronics at all.”

If the Director noticed the venom in Keelut’s voice, he ignored it. “Jason has a right to be proud: its a big triumph for our team”. Jason smiled.

“Indeed” Keelut agreed, with his most neutral voice.

“But I’m not here to chat with you, Mr. Okpik.” The Director turned his back to Keelut so that he could face Jason full on. He said, “Mr. Ungalaaq, I’d like to meet with you in my office for a moment. I have some personnel questions.” They left together.

Keelut left the lab in the opposite direction from his superiors, in order to take a short cut back to his office. When he arrived he saw that this morning he would have no peace: his academic sponsor, the Chair of the University of Inuvik Classics Department, hovered beside his desk. The Chair wore a faded yellow sweater vest, woolen jacket and pants, all made of very expensive, but well-worn materials. He wasn’t poor, but he was shabby.

The Chair addressed Keelut as he shook his hand. “Good morning, Mr. Okpik. Have you found anything yet?” He sat down in front of Keelut’s computer terminal.

Keelut hesitated to answer.

“Tell me about one of your poetry fragments” The Chair had a way of incrementally extracting information from the people with whom he spoke.

Keelut took a seat in front of his computer terminal, but still hesitated to answer. Although the Chair was a supporter of Keelut’s work, he was a political animal. Keelut took care about what he said to him and how. “I’m not certain where to begin”, he said.

“How about with a user name?”.

“The profile I’ve been reconstructing has the user name Capitalist Hero”.

“I see. Was this hero an industrialist, then? Perhaps he was from a noble family?”

“I don’t know. They didn’t store information about rank back then.” The Director hrmphed at the thought of such odd behaviour. Keelut continued, “But I know he styled himself as a poet.”

The Chair sat up straight in his seat. He had an entropic posture that tended toward a slouch when unattended. He asked, “Was Hero a poet?”

“I don’t think so, but he quoted famous poets frequently in his courting letters. He often took credit for penning their words himself.”

“How did you find him?”

“Shakespeare’s 76 Sonnet.”

“All of it or one stanza?”

“This stanza.” Keelut handed the Chair his note pad on which was written the words,

Why is my verse so barren of new pride,So far from variation or quick change?

Why with the time do I not glance aside

To new-found methods, and to compounds strange?

“This is excellent news, Keelut.” The Chair was exuberant. “Please send me a copy of all of your notes. Separate the poetry fragments. They’re what I’m really interested in.”

“Give me until tomorrow. I’d like to finish my analysis of Hero. He wrote a lot of letters.”

“Very well.” The Chair departed with a quick handshake and goodbye.

Left alone at last Keelut dove into his work. Hero had sent over 7,000 letters – ten per day for two years. Keelut sorted the letters by recipient name to see if Hero had courted the entire alphabet. He never found out. His eyes were drawn to the letter Hero had written to a woman named Tanya. It took no time for Keelut to pull up her record. The profile picture was of a buxom, but skinny, bikini-clad woman stretching on the hood of a metal wagon. Her tag line was “Hot Tanya loves cars.” In the About Me section Hot Tanya wrote,

Hi, I’m a car model so that gives me high standards

What kind of car do you drive?

I’m looking for some action with a guy who wants to race through life with me on his arm.

Catch me if you can!

It took one query to determine that Hot Tanya was one of the most popular women on the site. She had received more letters than Hero had sent

Keelut opened the one letter Hero had sent to Hot Tanya. The first paragraph was the same one Hero used for all of his introductions, but true to form the second paragraph related specifically to the profile of the woman he was courting. Hero wrote, “I’m a famous writer. You’ve probably seen my work produced on Masterpiece Theatre. When I found out your name was Tanya, it made me think of the sun, so I wrote this,

”But soft, what light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Hot Tanya is the sun …”

Keelut excitedly scribbled the entire fragment into his note book. When he was done he made another copy, which he carefully put into his bill-fold.

The day passed quickly. Keelut extracted over 200 unique fragments from Hero’s letters. He compiled the fragments into two categories – those he’d identified using the score of poetry anthologies scattered around his desk, and those he couldn’t.

When he had finally completed his analysis of Hero’s correspondence it was after 5:00 pm. The laboratory and surrounding offices were empty.

Keelut put on his suit jacket and overcoat, and then left. He headed straight to the Club. Tanya was not there. He asked several bouncers if they knew when she would next be working, and was told the manager who knew her schedule wouldn’t arrive until much later that evening. Keelut looked around. Each one of the dancers tried to trap his attention. He turned his back on them all.

§

When Keelut arrived at work the next morning he found the Chair of the Classics Department waiting by his desk. The Director of the Institute had scheduled a meeting for 9 a.m.. This was not good news: the Director had a reputation for making big decisions while in bed at night, and implementing them first thing the next morning.

Keelut and the Chair were greeted at the entrance to the Director’s offices by a butler, who took their coats and showed them in. The offices were decorated in a rich style. There was a thick rug on the floor, and the furniture was made of exotic woods. Every surface that could be burnished was.

They were shown to the ante-room, beside the Director’s personal quarters. It was lit by a large window that overlooked the delta of the Mackenzie River. Above the window was a stained glass triptych about the Passion of the Lady Diana: the first frame showed Diana’s pursuit by photographers, the second frame her escape in a metal wagon, and the third, her death. It was strange to see such an artifact in noble surroundings. The triptych was there because the building that housed the Ministry of Information had once been a pagan chapel.

When the Director arrived he shook the Chair’s hand and signaled to Jason and Keelut that they should remain in their seats.

The Chair and the Director took the throne-like seats on either side of a small wooden table near the fireplace. They unconsciously adjusted their ties after they sat down. They had gone to rival schools, Crescent and Artemis. Keelut sat on a studded leather chair at the other end of the room. Jason sat between Keelut and the Director, with his back to the window. Jason was also unconsciously adjusting his school tie. Like the Director, he was an Artemis man.

Tea arrived. Once they had all been served, the Director began the meeting by saying, “Mr. Okpik, tell me about your project.”

Keelut found the Director’s feigned ignorance sinister. He replied to the Director’s question in a neutral voice, “I’m working on a social networking database.”

“That’s right, the digital palimpsest.” The Director smiled indulgently.

“How so?” asked the Chair of the Classics Department. He didn’t understand the Director’s reference to a palimpsest. The Director smiled smugly. He said, “Explain to the Chair, Mr. Okpik.”

Keelut explained, “We found a networking database on an ancient file server that had been re-purposed by the Town of Burnaby’s Revenue Department. In that sense its a palimpsest – the artifact we’re studying is hidden underneath financial records that were added later.”

The Chair frowned but did not reply.

The Director spoke next, again addressing Keelut and pointedly ignoring the Chair, “Mr. Okpik, I understand that you’re looking for Shakespeare’s lost works?”

“Not just Shakespeare. Keats, Yeats. And also poets we’ve never heard of.”

The Director waved his hand dismissively. “Tell me about the site. What is it called?

The Chair tried to catch Keelut’s eye. He was mouthing something behind the Director’s back. Keelut didn’t want to know what. He knew it didn’t matter. The Director had made a decision. Nothing Keelut said or did would change anything. He said, “The site is called Finding Snookie.”

“What’s a Snookie?” The Director’s fake smile modulated into a faint sneer.

“Its an archaic pet name”, the Chair added helpfully. He had a perplexed look on his face.

“So this site helped people find lost pets?” Once again the Director spoke to Keelut and ignored the Chair.

“Not exactly. It was a dating network”, Keelut replied.

“How did the site work?” the Director asked.

“The network was divided into two groups, “Snookies” and “Captains of Industry”, or simply “Captains”. Although there were no rules about gender, most Captains were male and most Snookies were female. The goal of the site was for Captains to catch Snookies.”.

“By ‘catch’ I assume mean initiate sexual relations? This sounds like prostitution” . The Director’s words were harsh. His sneer, however, persisted.

Keelut replied, “I don’t think it was a prostitution site. At least not explicitly. Commerce was transacted in Snookie points, not actual currency …” Keelut quickly scanned the faces of his audience before continuing. The Director and the Chair were frowning. Jason had a smirk on his face

Keelut did not complete his sentence: the Director interrupted him, “Mr. Okpik, there is no need to continue.”

The Director turned to face the Chair, and now spoke as if Jason and Keelut did not exist. “Nerrivik, I’ve been dreading this decision. Let me be blunt. I’m not against trying to find lost sonnets, but because of the War I have to prioritize projects. Jason’s project …”

“The Wooden Internet?” the Chair asked.

“Yes, that’s what some of the junior officers call it. The project is showing great promise. Just this week, in Hangar 3, we recreated the functionality of an 8-bit central processing unit using only poplar, Douglas fir, some pig iron and one pound of copper. Nerrivik, in comparison your project …” he cleared his voice with a stage Ahem. “… frankly, it’s frivolous.”

Even though the Director was senior to the Chair, they were equal in social rank. Keelut expected the Director to put more effort consoling the Chair, after killing his project. Instead the Director turned his back to the Chair, and once again recognized the existence of Jason, to whom he said, “I’ll give you a week to come up with a decommissioning plan. I have every intention of returning to this project, but after the War has been won. We’ve already discussed our plans to redeploy Mr. Okpik to Hangar 4.

The Director concluded with a “Good day gentlemen”, gathered up his belongings, and then retired to his office.

§

Keelut was given the day off. He couldn’t have worked even if he had wanted to: his laboratory was occupied by Information Security. It was just as well. For all of his curiosity about the poetry fragments he would never find, all that he could think about was Tanya.

He went for a walk. He wandered without any particular direction in mind, so eventually wound up at Liberty Square, where students were protesting the undeclared war against Alberta. The protest had been going on for days. Many of the protestors were living in a tent city. Their tents were huddled around an ancient oak tree in which sat a large, black raven. Keelut arrived just as a rally was about to start. Because of his suit, tie and saber he was initially taunted for being a war-mongering Patron. But it was not an angry crowd. Keelut’s frank curiosity and open manner caused one protestor to engage him; when that failed the rest left him alone.

He had been looking at Tanya for a minute before he saw her. She wore sneakers, jeans and a t-shirt. Her blue jacket made her grey-green eyes look aquamarine. She was standing in the front line of a chorus of protestors who were singing the hymn Give Peace a Chance. The moment she saw him, she extended her right hand to him; he grabbed it. This created an awkward moment. They both realized the gesture asked the question, which way? Because of his work, Keelut could not join the protestors, so instead Tanya stepped out of the choir to stand beside him.

“Its nice to meet you here” Keelut said once Tanya had composed herself.

“You mean its nice to meet me again, don’t you?” Tanya spoke boldly, but her body language was guarded.

Her words flustered Keelut. “Of course its nice to see you, but I mean its nice to see regular people expressing their views in public. Too often people sit back and let the nobility make all the decisions.” As he spoke, he stepped backwards, away from crowd. She followed him.

Tanya said, “I’ve been meaning to call you. But …” she let the sentence lapse. She didn’t know how to say that she hadn’t called him because she didn’t know how – or whether – to upset convention. Crossing class boundaries was asking for trouble. Even if she was on the other side of the divide simply because her mother had been shunned by her family for marrying someone genetically modified.

She asked. “Why are you smiling?”

He replied, “I was thinking about having a long lunch.”

“With me, you mean. That’s a good reason to smile.”

He nodded.

The square was ringed with saloons. To get better food they decided to walk several blocks to a fashionable restaurant near the Mackenzie River. The roads were muddy, so Keelut frequently found himself shielding Tanya from passing carriages. They walked close enough together that they frequently touched, but they did not hold hands. When she spoke, she spoke softly, so was difficult to hear above the street noise. Several times they stopped while she held his arm and whispered words into his ear.

When they arrived at the restaurant there was an awkward moment when the host began to seat them in the Patrons’ section. Keelut handed the host his saber, and insisted that he wanted to sit in the Common area instead.

The host kept looking at Tanya as if he couldn’t understand why a Gentleman wanted to be seen in public with her. Finally, the host accepted Keelut’s sword; he seated the couple in a large booth beside a window.

The light was shining in on an angle. Keelut sat in the shaded side of the booth while Tanya sat directly in the sunlight. To shield herself, she half-opened her parasol and placed it in the window sill. The parasol tinted her skin rose-red.

They ordered two lager beers and some comfort food. The waiter quickly arrived with their food and bill. Tanya paid before Keelut even noticed.

When the waiter withdrew, Keelut judged that his moment had come. He said, “Yesterday I found a fragment of a poem written to someone with your name.”

Tanya beamed. “Read it to me.”

Keelut removed the poem from his billfold and clasped it with both hands.

His face was close enough to Tanya’s that he could feel her breath. He read,

But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Tanya is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief

That thou, her maid, art far more fair than she.

There was nothing more to quote, so Keelut put down the poem and placed Tanya’s hands in his. They were still holding hands when they exited the restaurant one hour later. It was twilight. The envious moon was rising in the south. Even now, in its ascendant glory, it could not compete with the beauty of the sun.

03 The Doctor Returns

“The Doctor returned last night”. Harriet fluffed her mother’s pillow, carefully pulled back one corner of the duvet cover, and then helped her mother up from her wheelchair onto her bed. The transfer was an effort for both women, so it was a moment before their conversation continued.

Mother spoke next, ”I’m so glad he got back safely. I don’t know why he goes on those dangerous voyages when his daughter is still a child.”

”He’s the Anderson’s top scientist. I imagine he has to do what he’s told.”

He didn’t have to leave his daughter in the care of that brute he has for a brother-in-law.

“Jimmy is a brute, but Katherine takes good care of Caitlin.”

“Dutiful wife and sister.” Harriet spoke with contempt.

Thus far the conversation was to type: Harriet and her mother’s opinions about Doctor Hofstaedter and his family had not changed for years.

”What did the Doctor say when he saw Daniel in that awful cell; or was he too tired to notice? You know how tired people can be so good at not noticing.”

“He was plenty tired when he arrived. He looked terrible, like he hadn’t slept in months. But he noticed Daniel, alright.”

The conversation paused for a minute while Harriet’s elderly mother propped herself up, so that she was more comfortable. When she was done, Mother eagerly asked, “What happened?”

Harriet replied, ”The moment the Doctor saw Daniel in his cell he just stopped. His whole entourage stopped, the porters, his man, Caitlin.”

”His daughter was there?”

“Of course she was there. She hasn’t seen her father in well over a year! You couldn’t separate them.”

“She’s a sweetheart, isn’t she?”

” I sometimes fear that her heart is too good for this world.”

”She’s going to have to lose some innocence; the world’s certainly not going to get more virtuous on her account.

“She already has. Remember how she looked when her Uncle took the money she was going to use to bribe the auditor.”

Mom nodded in agreement then asked, “So what did the Doctor do?”

“For a long moment he didn’t move. I didn’t even see him breathe. It was like he was trying to find the energy to do anything at all. But when he moved again, he moved quickly. First he whispered something to his man, who disappeared up the stairs with the porters in tow. Then he told his daughter to go to bed. After that he turned around and marched out the door.”

“What did Caitlin do?

”She followed her father, of course. She’s like her father very determined once she’s chosen a path.”

“It took almost an hour for the Doctor to return but I didn’t notice the time because the foyer was filling up with people. Every time someone new arrived I had to tell them the story all over again.”

“What about Mrs. Ellison?”

“She was standing on the edge of the foyer. Bruno was with her, of course.”

Mother nodded as she pictured the scene in her head. After a sip of water, Harriet resumed her story.The Doctor returned with his daughter and a blacksmith. By this time his eyes were dark red and his hands were so unsteady that Caitlin had to open the door for him.

“Had he been drinking?”

“The Doctor never drinks!”

“Habits change, daughter. Tell me more about Mrs. Ellison.”

“Be patient, Mother. I’ll tell you about Mrs. Ellison when it matters.”

Harriet straightened her skirt, and then continued, “The Doctor walked straight to the cell, past Bruno, Mrs. Ellison, everyone, as if we didn’t exist.”

”Harriet, I’ve known Doctor Hofstaedter since he was a child. Be certain he knew everyone’s location and rank.”

Harriet ignored her mother’s comment and continued. She said, “The Doctor stopped one step before the cell. He turned to face Bruno, his hand on the hilt of his saber, ready to draw. The locksmith and Caitlin were behind his back. The locksmith fired up a gas torch. He could have picked the lock, but the Doctor had ordered him to break the gate into pieces.”

Mother laughed and clapped. “What wonderful news! Why that’s the best news.” She quickly became serious. ”Harriet, if your father had lived, this whole episode with Daniel would never have happened. You know that.”

Harriet nodded her head obligingly. She didn’t know that, but liked to share her mother’s dreams about what might have been.

Mother asked, ”What happened to Daniel?”

When the gate to his cell was destroyed Daniel immediately ran out and cowered behind the Doctor. Bruno tried to intervene, but when the Doctor drew his sword , he thought better of it and backed off toward the door.”

“What about Mrs. Ellison?”

“She was screaming that Daniel’s imprisonment was legal, that he was a hoarder, and that his imprisonment was a mercy because he should have been hanged for what he did.”

“Such a fight, in such a small space.”

“It was like a stage at a theatre. Everyone but the main actors had run up to the mezzanine or out into the street to watch from a safe distance.”

”Did Bruno attack the Doctor?”

“Bruno was carrying a large wrench in his right hand – the one he uses with the boiler. You could see him trying to decide whether to attack the Doctor, and mark my words he was going to, when the door was pushed open by the Doctor’s man, who had arrived with two tough looking friends. I don’t trust that man, but I understand now why the Doctor retains his services.”

Mother nodded and Harriet continued speaking, ”The Doctor stepped toward the entrance to join his people. Caitlin and Daniel were one step behind. They formed a line at the door. The Doctor was in the center. His daughter was on his left side, in front of the stained glass window. The Doctor’s man and his ruffian friends were by the entrance to the mud room.”

“Where was Daniel?”

“While they were gathering at the door, Daniel slipped out and ran away. He didn’t even have shoes on.”

“What happened next?

“It was the Doctor’s show. Even though he was so weary he could barely stand”. He said in a public voice, ‘Why was Daniel imprisoned?’ It was like the beginning of an ancient Greek trial.”

“How do you know that?”

“Mother!”

“Alright, so tell me about Mrs. Ellison.”

“Mrs. Ellison was standing at the foot of the stairs under our License. She said, ‘Its like I’ve been saying, the prisoner is a hoarder. There’s a war on right now, and he had a sack of rice he wasn’t sharing. There was a fair trial and he was convicted. We should have executed him.’”

“What did the Doctor say to that?” Mother asked.

“He ignored Mrs. Ellison. Instead drew his sabre and pointed it at Bruno and asked in his most proper voice, ‘Who is this man?’ Bruno stepped into the middle of the foyer, two paces from the Doctor. He bowed and said, ‘Bruno Constantinus, at your service’.”

Bruno can be polite? Mother asked caustically.

”He brandished his wrench before he bowed”, her daughter replied.

“Didn’t the Doctor’s man do anything?

“He moved to block Bruno but the Doctor signaled for him to back off. But let me finish! After Bruno introduced himself, he walked right up to the Doctor and said very politely, Mister, you are upsetting the Lady.”

”Lady…!”, Mother laugh while she slapped her knee.

Harriet nodded, ”You’re of the same mind as the Doctor. He took two steps sideways – toward the entrance and away from his people – and shouted so loudly he could be heard across the street, ‘This man is calling Mrs. Ellison a Lady! Hah! There is nothing noble about that woman!’”

”The Doctor was making room for his sabre, wasn’t he?” Mother asked.

Harriet nodded. “Then Bruno did something very stupid.”

“The poignard? Mother hazarded, with a worried tone in her voice.

Harriet nodded, ”Bruno pulled back his cloak to reveal that rusty knife he calls an heirloom.”

Mother used her pillows to raise herself half way out of her bed, “Oh no. Bruno didn’t … ?”

“The instant Bruno placed a hand on the knife the Doctor killed him with one cut through the heart.”

“In front of Caitlin! Poor child. Is she alright?”

“I don’t think so know, but she can’t be. As Bruno collapsed she smiled that flat terse smile of hers.”

“Her secret smile. What about Mrs. Ellison?

“When Bruno died Mrs. Ellison went crazy. She started shouting at the Doctor, and pounding her fists against his chest. She went on about food shortages and how dangerous hoarders are, and how letting one person get away with crime encourages everyone to try.”

“What did the Doctor do?”

“He didn’t do anything, he just studied Mrs. Ellison, like she was a specimen.”

Mother laughed.

Harriet continued, “Guess what happened next? Two policemen showed up!”

Mother was so thrilled the story had another chapter she slapped her palsied knee again. Her daughter continued, “The Doctor was the person with the highest rank at the scene of the crime, so of course he explained to the officers why there was a corpse. The police accepted the Doctor’s claim that he had killed Bruno in self-defense. One policeman actually ticketed Bruno for possessing an illegal weapon. He said, ‘That’s what happens when commoners wear swords.’”

The policeman’s comment fired Mother up. She said, “That cop is an ass. Bruno was just too stupid for his weapon.”

Harriet smiled at her Mother but her narrative did not miss a beat, “You won’t believe what happened next. Two more policemen entered with Daniel, handcuffed, between them.

”What did Mrs. Ellison do? She she try to show them the court records?”

“She wanted to say something. She stood right behind the Doctor, muttering to herself like she was practicing her lines.”

“But she didn’t?”

”No. The Doctor didn’t give her a chance. He was very civil. He invited all four policemen to warm themselves by the coal heater, and sent his man upstairs for drinks. The newly arrived policemen said that they were here because they had found Daniel, without any shoes, at the carriage depot. Because he had been branded with this address, they suspected he was a felon or escaped slave.”

“As his man handed the policemen drinks, the Doctor informed them that Daniel had been a prisoner here but new evidence had come to light, and he was now free.” Harriet imitated the Doctor’s formal style of speech as she recounted his words. ”He gave the officers extravagant gratuities and asked them to please ensure Daniel got shoes, a change of clothes and a coach ticket to Anchorage. The Doctor asked for their names and ranks to ensure compliance. As the policemen left, the Doctor shouted after them in a loud, hearty voice, ‘Officers, I will commend you to the Anderson.’”

”That’s so like the Doctor”, Mother said drily.

Harriet continued, “As soon as the policemen were gone the Doctor shooed everyone out of the foyer promising that everything would be set in order at the next board meeting. He had his people take care of Bruno. They did a good job. There’s no sign of blood at all.”

”That’s quite a story, Harriet. Did it really happen or is that pitiful man still imprisoned under the stairs?”

”Daniel’s free Mother. He’s at his parent’s house in Anchorage.”

Mother reached over to clasp her daughter’s hands in hers. ”Harriet, I fear that my generation has let you down: we’re leaving you a world far worse than the one we inherited. Just like our parents and grandparents did.”

”Nonsense Mother. The Doctor is back. All it takes is a few good people to turn everything around.”

”Harriet, there are never enough good people.”

04 Lots

“Skinny.”

Jimmy threw a handful of dust at the girl and shouted again. “Tanya is skinny skinny skinny.”

Although the epithet was appropriate, Tanya was thin as a rail, it was the kind of insult a black pot might hurl at a kettle. At eleven years Jimmy showed his age: he was scrawny, like a sickly rake, except at the point where his belly distended through his ragged t-shirt; his lips were thin and his eyes were dull; his skin was puce-coloured and filthy. As with far too many boys in Fairbanks, it was difficult to tell where dirt ended and disease began.

Tanya stared down at Jimmy but didn’t reply to his taunts. His words didn’t hurt as much today as they did on other days. Today she felt distanced from him, as if she was from another world that he couldn’t touch.

Two blocks from Tanya’s home Jimmy made a left so that he could take a short cut to his home in the Projects. Tanya turned right, and began walking toward the other side of the railway tracks. Her mother was waiting for her on the stoop of the family’s three story brick townhouse. Normally, that was a bad sign because it meant Mum wanted to talk about something, like grades. This time Tanya wasn’t so sure. Her mother didn’t even notice her approach: she sat crouched forward with her head between her hands, looking down at her feet. In her left hand she held a rumpled, blue envelope.

“Mum.” Tanya asked tentatively when she reached the bottom step. Her mother hadn’t even noticed her arrival.

Tanya’s mother looked up and wearily said, “Hi Pumpkin.” As an afterthought she added, “How was school?”

“Fine.”

“Were you on time?”

“Yes.”

“Did any of the Hootch boys bother you?”

“Yes”

“Which one?”

“Jimmy.”

Mum sighed, “What did he do?”

“Nothing.”

Mum let it drop. At least she wasn’t crying anymore. Tanya said, “Come inside, Mum. I’ll help you make dinner.”

Dad arrived two hours later, at 6:00 pm, which was early. Mum greeted him at the door. She hugged him until he gently pushed her away. He said, “That’s enough Rhonda.” He wasn’t annoyed by Mum’s excessive affection, just tired.

Dad walked into the kitchen. He silently stared at the bare table – a small plate of potatoes, and some salmon. He asked, “What’s for dinner?”

Tanya braced herself. Dad could see what was for dinner. But he wasn’t asking a question, he was saying how little there was. He always did that, because where he came from in California there was lots. In Fairbanks there was never enough.

Mum was in no mood to fight. “You’ve got some mail.” She handed Dad the blue envelope she’d been crying over earlier. Dad looked at the envelope. He noticed it was opened but said nothing. He handed the letter back to Mum and said, “Read it to me.”

Mum whispered, “Tanya’s here.”

Dad said, “Read it anyway”. He didn’t lower his voice. Mum read,To: GM visa holderUnder the terms of Article XIII of the Genetic Purity Act, you are to report to any Republic of Alaska military recruiting centre within two weeks. Failure to do so will result in an immediate felony conviction.

A list of recruiting centres …

“That’s enough.”

Mum stopped reading.

“What’s a GM visa, Dad?” Tanya asked.

“Your father’s genes have been modified to make them better” Mum replied.

“When? Why wasn’t I told?”, Tanya exclaimed.

“The changes happened hundreds of years ago, pumpkin” Mum replied. “Your father inherited the improvements from his Mum and Dad.”

“And you inherited them from me”, Dad added gruffly.

Mum raised her voice so that she could speak over Dad, “Your genes don’t matter right now, Tanya. What matters is that your father has to join the army for a few years.”

“Do we have to move?” Tanya asked.

Dad answered, “Yes. I’ll be training at Fort Palin, near Inuvik. That’s where they send all the conscripts.”

“What about the war?” Tanya asked her father. “Do you think you’ll have to fight in the war?”

Mum spoke with an outdoor voice, “There’s no war! That’s just a border dispute over Lake Athabasca. I’m sure it’ll be over by the time your father’s training is done.”

Dad picked up his food and went to the living room. That’s what he did when he was angry but too tired to fight. Tanya went with him. Mum stayed in the kitchen. She hardly ate.

When Dad finished his dinner he went to the kitchen to talk to Mum. He wasn’t angry anymore. Tanya pretended to sleep by the stove, but was really listening to her parents.

Dad said, “Rhonda. I’m going to go back to Long Beach. I’d like you and Tanya to come with me.”

Dad looked at Mum. She looked away. She said, “Cody, draft dodging is too dangerous. If you get caught you’ll be shot or enslaved. And think of Tanya.”

Dad looked into the living room.

Mum said, “Do you think two years in the army is that bad? I bet the pay is the same as you get now.” Mum was speaking quietly. Tanya rolled over so that she could hear better.

Dad replied, “Sure. Soldier’s make more than labourers. If they live.”

Mum started to cry. §

Just before dawn Tanya awoke and quietly descended from her room on the third floor to the kitchen to make breakfast. She found Mum sitting on the couch in the living room. Mum’s eyes were bright red but she was no longer crying. Tanya hesitated before joining her. She didn’t know what she could say: she disliked it when Mum asked nosy questions, so hesitated to do so herself.

Mum spoke first, “Did you do your homework?”

“No. I couldn’t think last night. Anyway, I have until Monday.”

“What’s your assignment?”

“Its like show and tell. I have to pretend I’m a visitor from an historical time and place.”

“Do you have any ideas?”

Tanya shrugged, “Miss Langan said I should talk about the Arctic War.”

“Don’t talk about war, sweetheart. Do something cultural instead. Why don’t you talk about the Movies?”

Tanya liked that idea a lot more than talking about some ancient battle. “That sounds great, Mum, but I need a theme.”

“What do movies make you think of pumpkin?”

Tanya thought about the fights between Mum and Dad over how there was never enough food.

“Lots”, she said.

“What do you mean?”

“They had lots of everything in Movie Times. I’m want to talk about that.”

Mum leaned over and gently clasped Tanya’s hands, “How about we study tomorrow by seeing a movie?”

For the first time in weeks both Rhonda and her daughter smiled. §

The next morning Rhonda and Tanya got up early for the walk downtown to the Central Reference Library. The road had just been cleaned, so they walked on it instead of the rickety wooden sidewalks. They had to be careful to avoid getting splashed by delivery wagons rushing to the Saturday market.

Tanya, though quiet, was engaged. Every once in a while she would make a comment about something, but otherwise was content to look everywhere and say nothing.

They arrived at the library on time for the noon matinee. Today’s movie was “Harry Potter and the Temple of the Phoenix”. The library always played this one because it had lots of copies, so it didn’t matter so much if one wore out.

Tanya was bursting with excitement. Despite herself Rhonda was as well. It had been years since she had seen a movie, and she had never once seen a Harry Potter.

The theatre was part of a Victorian Revival building that had been annexed to the Central Reference Library a generation earlier. Its entrance was guarded by a pair of marble dragons, which sat on either side of a grand staircase. Its atrium was illuminated by a giant electric light that hung from a domed ceiling. The theatre itself had an orchestra pit and two terraces. The staircase walls were painted with giant frescoes of important moments in the military history of the Republic: the battle of Bear Lake, the lifting of the Siege of Barrow, and the sack of Burnaby. The second balcony was closed entirely while artists worked on the latest addition to the frescoes, a memorial to the Hay River Massacre. It was a painting of the young Joan Smith dying on the bow of the Mackenzie Dawn. That was the event that started the current war.

The movie began.

For both Tanya and her mother the next hour was a wonderful blur.

When the torches were lit for the intermission, Tanya became disoriented. The Dementors, Hogwarts, the magic – it was all so vivid. The library auditorium seemed flat, dull and unreal. §

Tanya went into the lobby to buy a soda for her mother, and some popcorn for herself. Mum eye’s followed her as she went.

The concession stand was decorated with mirrors. All of the walls and pillars had mirrors as well, which made the lobby look huge because every where you looked you saw infinity. Tanya was teased so much about her body she never looked at herself in the mirror. Why would she want to see how ugly she was? She tried not to look at herself now, but it was difficult.

While Tanya stood in line, staring at her feet, a child’s voice said, “Miss. Miss.” A little girl, no more than seven, tugged at the hem of her skirt. Tanya looked up. The tugging was being done by a beautiful Yupik girl – she was well fed and had ruddy red skin. Her black hair was tied into two pigs tails that stuck up like antennas. The child asked Tanya, “Miss, are you Hermione?”

Tanya looked from the girl to millions of reflections of the Hermione.

The Yupik child burst out, “You’re beautiful!” The little girl was so embarrassed by her words that she rolled away, but the words she had just spoken did not leave with her. Tanya wouldn’t let them: she had always wanted to be beautiful.

A woman wearing a puffy coat made of muskrat fur rushed over to Tanya. She bent down on one knee and raised Tanya’s chin with her right hand, and said, “That Eskimo child is right. You look just like Emma Watson. Are you one? I haven’t seen any since the pogroms.” Tanya edged away, but there was nowhere to hide in a room full of mirrors. The woman continued, “Never mind. Of course you are. Why don’t you read this. There’s an address on the back if you want to talk.” The woman handed Tanya a pamphlet. There was a black and white picture of the magician Hermione on the cover. It had the title, “The Goddesses of Movie Times.”

Tanya took the pamphlet from the woman, and rushed back to her seat. Mum didn’t ask why Tanya didn’t return with a drink.

In the last few moments before the movie continued Tanya began read a story from her pamphlet with the title “Were wizards real?”

Mum noticed but said nothing. §

The moment the movie ended Rhonda threw a hat and scarf over her daughter, hustled them both out of the library and onto the street. Despite the cost, they took a carriage home.

For the first few minutes of their journey they were both silent. Tanya was thinking about how Hogwarts was her true home, and wondered if there was a portal to it in Fairbanks. She once excitedly made the driver stop the carriage when she mistook a huge, unkempt trapper for Hagrid.

Rhonda brooded, uncertain how to proceed.

Tanya broke the silence, “Mum, am I Hermione?”

“Dear heart, someone hundreds of years ago altered your genes so that you look like Hermione. But no, you’re not her. Hermione is not real. She’s just a character in a story.”

“But what about Emma Watson? She was real. Am I her? Or a clone of her? Or something else?”

“Pumpkin, movie stars are never real. They’re myths we create about famous actors.”

“Why?”

“Why what?”

“Why would someone want to look like Hermione?”

“Because she was beautiful.”

Tanya tried to suppress a smile; she did not succeed, “But I’m skinny.”

“In Movie Times people thought it was beautiful to be slender. They considered it a sign of health and self-discipline.”

“What do you mean, self-discipline?”

“Back then there was so much of everything that some people had too much. They would eat and eat until they grew so fat they were ugly.”

Tanya remembered how Dad looked at his empty plate.

Too much and not enough. §

When they got home Tanya and her mother silently prepared and ate a simple meal. Dad wasn’t there: he worked on Saturdays.

When they were almost done cleaning up dinner Tanya broke the silence. “Mum, I’ve been thinking about my presentation for school. Can I practice on you?”

Mum said, “Of course, dear.”

They put away their towels, drained the sink and retired to the living room.

Mum sat down in the big chair Dad always used. Tanya gathered her thoughts while she composed herself in front of the wood stove. She had learned from the Harry Potter movie that she wasn’t an ugly duckling. If this was California in Movie Times everyone would think that she was as beautiful as a star. She had to let her classmates know this! But how?

Tanya began, “In Movie Times make-believe was real, and because we make-believe wonderful things everything was better back then.”

Mum squirmed in her chair.

Tanya continued, “They had lots of everything in Movie Times. Not just clothes and wagons, but even lots of fresh water. They had machines that could create water out of air.” She took a big inhalation. “And of course they had lots of Movie Stars.”

Tanya stopped speaking. That was as all she had.

Mum carefully asked, “Tanya, what did you say about make-believe?” The simple question confused Tanya. Tanya had gone into a trance when she recited her speech. She didn’t remember any of it, what she had said, what Mum’s reactions were, nothing. She said, “Let me practice some more, and do some research. We can do it again tomorrow. OK?”

Mum nodded.

Tanya went to bed, where she dreamed of eating all the smoked fish she wanted, and having lemonade and sugar cookies for desert.

Mum was hungry. She had scrimped on dinner because the cost of the carriage home had been steep. She opened the icebox. All they had was a small piece of dried salmon, some old potatoes, stale bread and sour butter. She left it all for Dad. §

On Monday morning Tanya was excited about how she was going to tell her story. She knew that if she could make her classmates understand that she wasn’t just different she was special, like a princess from a far away land, they’d be her friends.

Rhonda looked at her child. Tanya had never been this enthusiastic about going to school. Had she ever been this enthusiastic about anything? Tanya’s excitement took the edge off her mother’s nerves, but it was impossible not to worry. They had rehearsed the presentation a dozen times last night, and each time Tanya’s words were different.

Although she was shunned by her family, Rhonda Anderson was still treated as a highly ranked noble by the teachers at her daughter’s school. When she arrived with her daughter in a carriage, which they had taken to ensure that Tanya was unmuddied, a great fuss was made by the principal. Rhonda was invited to watch all of the presentations. Although she was anxious about her presence upsetting her daughter, she agreed to stay.

The school had three classrooms for three different age groups. All the children had all gathered in the biggest classroom, which was the one normally used by the youngest children. Tanya’s teacher was a middle-aged Asian refugee who had migrated to Alaska across the pole. Her English was fluent, but accented, and precisely spoken. This gave her an appearance of harshness not warranted by her otherwise stoic and gentle manner. She was dressed in a blue uniform, white top and blue tie: an adult version of what the children wore. The school bell rang; the children settled down.

The teacher asked, “Who would like to go first?”

Tanya’s arm shot up. Her teacher was surprised. Tanya was a reticent child who never volunteered for anything. She said, “Very good, Tanya. You can go first. What is your historical period?”

“Movie Times.”

“What is your theme?”

“Lots.”

“I expect you to explain what you mean by that.”

Tanya nodded vigorously but wondered why you’d need to explain the idea of lots to anyone.

Tanya took her place at the front of the classroom, stood up straight and smoothed her skirt with her hands. The teacher said, “Begin”.

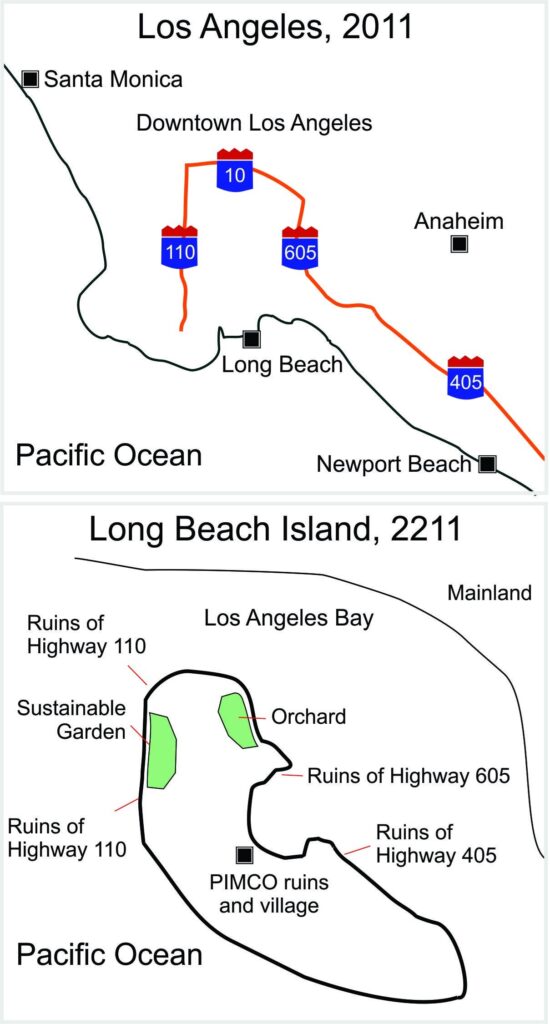

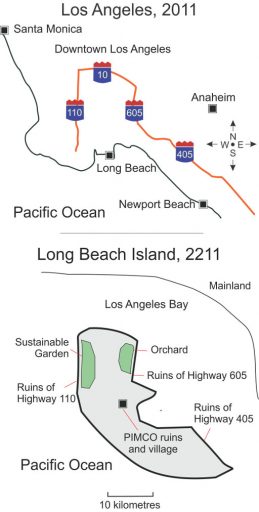

Tanya began. “My speech is about my pretend visit to Los Angeles, California in Movie Times.”

Tanya mustered all of her effort to look at her classmates. She wouldn’t go blank the way she did when practicing with Mum. They were all looking at her. Tanya’s heart was racing. She took a deep breath to calm herself down. She began, “In Movie Times there was lots of everything. There was lots of lemons and sugar, and crayons came in over one hundred colours.”

Tanya nervously inhaled. She exhaled, “The streets were full of metal wagons with tires made of air. Every family had one, some had two or three, so that children could drive too. At first I was scared to drive, then one day I drove from Hollywood to Santa Monica on a highway. It was fun.”

Tanya paused to look at her classmates. She had their complete attention. She smiled as she spoke her next words, “Even school was fun in Movie Times. There were no tests because everyone owned a box that contained all knowledge. If you wanted to know something, all you had to do was ask your box. It was easier if you could type, but you didn’t have to, most of the time the knowledge box could understand your spoken words.”

Tanya’s audience had disappeared. She was entirely in her head again. This time, she noticed. Pay attention, Tanya, she thought. This can change your life.

Tanya forced her perceptions to come back into the room. In a bold voice she said, “One of the best things about back then was all the Movie Stars. There was Halley who was the goddess of beauty. She was thin and had big breasts, so everyone liked her.”

Tanya looked at her classmates, just to know she could. She continued, “Not all of these goddesses were good. Some were terrible. The goddesses Paris and Lindsey and Britney used to kill their boyfriends, after they kissed them.”

“My Mum thinks they still do.” That was Jimmy Hootch. For once he wasn’t teasing. He was just saying. Tanya felt encouraged. She said, “I think so too”. Mum cringed.

Tanya’s presentation reached its climax, “On my trip to Hollywood I met my favorite movie star, Emma. That’s her regular name. Her Greek name is Hermione. I liked her because …” Tanya stumbled on the words because Emma was just like me. Tanya couldn’t say that. Instead she said, “Hermione was one of the perfume goddesses.”

“What did she look like?” The question was asked by Peter, one of the older Hootch boys. Today he had a large bruise around his left eye. Just like the one his brother Jimmy had last week.

“Let me tell you” Tanya said proudly. She opened up the pamphlet she had been given at the Central Reference Library, and began to read in a loud, steady voice, “The goddess Emma was pretty and thin and had small breasts, a pert butt and a button nose.”

“Tanya, did you see the Harry Potter movie on Saturday? You look like the magician Hermione.” The question was asked by one of the older boys who Tanya didn’t know.

“Yeah, you do.” Everyone who had seen any of the Harry Potters agreed.

Even though Tanya was afraid of expressing her emotions, a smile spread over her face. She had done it! Now they all knew. She wasn’t an ugly duckling because she was skinny. She was as beautiful as a movie star.

“Why don’t you see if anyone has questions?”, the teacher prompted.

“I have a question. I do.”

“Calvin …”

“Tanya, what was the best part of Movie Times?”

Calvin was the oldest of the Hootch boys. He was quieter than his other brothers, as if age had made him too tired to be angry. He got more black eyes than the rest of his brothers combined, even though he never fought.

Tanya replied, “I think that the best thing about back then was that no one ever starved, because if you got hungry and had no food the Government gave you stamps that you could eat.”

Calvin’s eyes went wide. Tanya looked at the rest of her classmates. All of their eyes were wide too: their next meals were never guaranteed. They had all gone hungry.

“Are there any more questions?” the teacher asked.

There were no more questions. The children had learned all about lots.

08 The Battle of Tar Island

“Your father is from Russia?”

“Yes.”

“Military visa?”

“Yes.”

“You volunteered?”

“My family is patriotic, Sir, I mean Ma’m.” This was mostly true. Anton’s mother, a Daughter of the Alaskan Counter-Revolution, and youngest child of a Patron, was in every way a patriot. His father had retired from the Alaskan army as an officer, but had joined it as an immigrant mercenary.

“I see.” Colonel Hoefstaedter looked at Anton’s dossier again. She said, “You’re genetically modified. Are you one of the smart ones?”

“An ancestor had something done about anemia. It was a common procedure two hundred years ago. Its all in my record.”

As the Colonel flipped through Anton’s dossier, she said, “I didn’t think cases like yours were covered by the Purity Laws”.

“They cast the net a little wider each year.”

The officer then did something that surprised Anton. She said, “I apologize for even mentioning it.

“No offense taken.”

“Let’s get down to business. You have been given a special assignment.” She paused, which he took as an invitation to respond.

“It’s an honour, Ma’m.”

“You haven’t heard your assignment yet.” The Colonel didn’t say this in a disparaging way. Whether she liked him or not, this man was a natural ally. That was more than she could say about the conscripts.

The Colonel rose from her chair, “Lieutenant, you will be briefed in full by military intelligence, but I want to talk to you personally about this assignment. You know that we’ve launched an attack along the Peace River?”

Anton nodded.

“That’s only part of our strategy. If we don’t control the factory and mine at Tar Island, just north of Fort McMurray, on the Athabasca River, controlling the Peace River does nothing for us.”

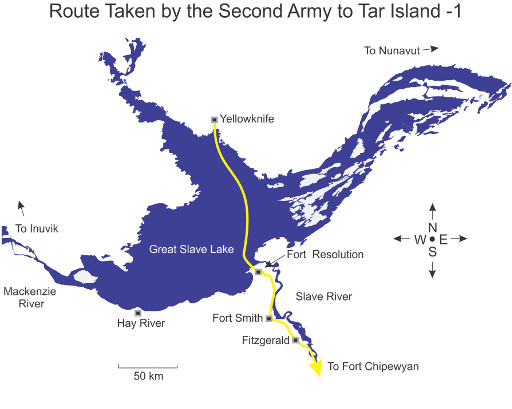

The Colonel escorted Anton to the large map of Alberta that was hanging on the wall opposite her desk. She pointed to the northern tip of the map, “Our first attack is happening right now, here.” She used a wooden pointer to describe an ellipse around a city called Fort Vermilion that was several hundred kilometres west of Lake Athabasca, on the Peace River. “That’s to protect our flank. Our second attack, the one that you will be participating in, will be here. She drew a line south-east from Yellowknife, through Lake Athabasca to Fort McMurray. “If we win both battles then we’ve secured our complete objective. If things don’t work out, our armies can reinforce each other as they retreat.”3

“Why are you telling me this?” Anton asked.

The Colonel circled back behind her desk. She used it to support what she said next. “As you probably know, the Republic’s Army, for the first time since Federation, has more conscripts than career soldiers. We’re having severe discipline problems. The General has asked me to create an informal network of trusted junior officers on whom he can count should issues arise.”

“Mutiny” Anton thought. He said, “I understand. Is that all?”

“No. There is still the matter of your assignment. Although your squadron will be part of the Second Army’s artillery corps, this will be only in a support role. We need you to survive.” The Colonel made this point as if she expected many people in the artillery corps not to survive.

“You know about the Alexandria Convention?” the Colonel asked.

Anton nodded.

She continued speaking as if he didn’t. “Normally we – the Albertans and the Republic – do not fight near Digital Age ruins. However, this battle is about one. Your platoon’s task is to occupy the control room of an ancient tar-processing factory. From the Republic’s perspective, that factory is worth an army.”

“I understand. I’ll be careful not to damage anything when I secure my objective.”

“Excellent.” The Colonel began to dismiss him, but then said, almost as an afterthought, “One more thing. I told you that you were one of a group of officers who are trusted by myself and the General. Your commanding officer is not one of them.” §

The moment Anton finished packing there was a knock on his door. He opened it to greet his commanding officer, Captain Shevetz. Shevetz’s people were from Russia too, but via a different trajectory than Anton’s father: they were political refugees and intellectuals who had emigrated to Alaska when Russia was still Communist.

Anton invited the Captain in. He assumed that Shevetz was here on platoon business, so was surprised when Shevetz began their conversation with the question, “Have you ever traveled?”

Anton looked at the man, trying to determine his point. There wasn’t much to go on. Shevetz was of medium build, had close cropped brown hair and eyes. He had a neutral demeanour that was easier to project on to than read.

Anton shrugged, “I went to Juneau once.”

“Have you traveled outside of Alaska?”

“No.”

“Not even to Yellowknife or Whitehorse?”

“No.”

“Do you have an opinion about Albertans?”

Anton replied, “Not really. I mean they’re the enemy. But I don’t think much about that. I like to focus on the positive side of patriotism, like glory and honour.”

“So you consider yourself a patriot? Don’t answer me as a subordinate, Anton. Tell me what you really think. I’m listening to you.”

Anton replied, “When I enlisted, my mother told me to be prepared to die for my country at any time. My father told me that the living are more loyal than the dead.”

Shevetz nodded his head. Anton wonder whether his commanding officer was agreeing with what he had just said, or was simply acknowledging it.

Shevetz continued speaking, “Your father was a officer, wasn’t he?”

“A Major.”

“Is he still alive?”

Anton nodded.

“He must be very loyal.”

Anton smiled. The Captain’s joke relaxed him.

Shevetz, however, was still on edge. He was impatient for this conversation to reach the destination he was directing it toward. He said, “Anton, have you ever fought before? I mean in a real battle with hand to hand combat.”

“I helped put down the Bottle-head riots.”

“What did you think when you shot your own people? Be honest.”

“I thought about the conflict between duty and patriotism.”

“Take this.” Shevetz handed Anton a small book bound in yellow burlap. Anton opened it. There was no title page and no publisher’s imprint, just text. Anton recognized the opening line, “Clients of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.”

Anton handed the book back to Shevetz. “I don’t need this. I can figure out what’s right and wrong on my own.” He spoke these words with more assurance than he felt. He wondered where his moral grounding came from. Certainly not from God and Country, like he was trained to say. No. His morality – like his patriotism – came from his family; from his mother, with blood as blue and cold as the Arctic Ocean, and his father, the mercenary.

Shevetz’s sharp voice brought him back to the present. “Lieutenant, if you worry too much about right and wrong you may forget to choose sides.”

“Captain, I also hope you survive the upcoming battle”, Anton replied.

“We can’t ask for much more than survival, given current circumstances.” Shevetz exhaled a sigh of relief. He rose to leave. At the door he hesitated, as if coming to a decision. He said, “Anton, on the morning of the battle, don’t wear your Bands.” The Officer Bands were glow-in-the-dark strips of material that allowed officers to be seen when visibility was low.

Anton noted Shevetz’s grim expression. “Thanks for the tip, Captain. Before you go, I have a question for you.”

Shevetz stiffened.

“Do you know what’s happening with the First Army? The last I heard they were stuck on the Slave River portage. Have they made it to Peace River yet? Have they begun the assault on Fort Vermilion?” I was a practical question. If the First Army had already failed their mission was doomed. But the question itself based based on information enlisted men did not have. He could see that Shevetz knew something, but Shevetz viewed the question as a trap. He started to say something, stopped, nodded his head glumly, and then took his leave without saying another word. Anton saluted his back. §

The Second Army mustered at Yellowknife because of its central location between Nunavut and Alaska. A ramshackle flotilla of boats ferried the Army across Great Slave Lake to Fort Resolution, a small tourist and industrial hub situated immediately west of the mouth of the Slave River, 500 kilometres north of their ultimate destination.

The ferrying across Great Slave Lake took the better part of two days, with the biggest delay coming from the horse barges, which could only travel when the lake was calm. The infantry spent one evening at Fort Resolution. The next morning they began a quick march south along the western shore of the Slave River. Although the population of the region was in decline, the farms that remained were prosperous enough to maintain the roads year round. The cavalry traveled by barge down the Slave River.

The cavalry met the infantry at Fort Smith, where the river barges had to empty because a series of four rapids rendered the Slave River unnavigable for the next 25 kilometers. The portage had been difficult for the First Army, which had passed through here four weeks earlier. The ground was scarred by the marks made by wooden skids. At Cassette Rapids they saw their first dead slaves, poor souls who had been left for compost on the cold, rocky ground.

The portage ended at the town of Fitzgerald where the entire army got onto barges and floated down the Slave River to Fort Chipewyan, on Lake Athabasca. Fort Chipewyan, surrounded by rivers, marshes and lakes, had never been a fully integrated part of Alberta. Its physical separation from the south was compounded by centuries of anger at how the Athabasca River, and the entire Lake, had been poisoned by the upstream mines. The Fort surrendered to the Second Army without a fight.

At this time of year, the arctic was much easier to reach than leave via Fort Chipewyan. The problem was that the western edge of Lake Athabasca was impassable except in winter; the Second Army had arrived in spring, after the thaw. The entire region was a marsh. With the persistence of men who have no authority but to follow orders or die, the soldiers began the tedious task of ferrying men, horses and ordnance south in barges, through the delta to hard ground 50 kilometres south of the Lake. The first convoy took 5 days to transport a fraction of the Second Army.

They were saved from a several month delay by a cold spell that made the winter road through the marsh suddenly navigable. Thanks to the freeze, the entire Army, save for a few slaves, cannons and horses, made it to the head of Highway 63 in one brutal, 36 hour march. From there it was a straight shot to the factory at Tar Island.

The pace was set at 20 kilometres a day, which for an individual soldier walking with a heavy pack through rough terrain was reasonable. For an army with cannons and skittish horses, it was extreme. Nevertheless, the demoralized soldiers kept to the pace: endless delays had made everyone anxious to move.

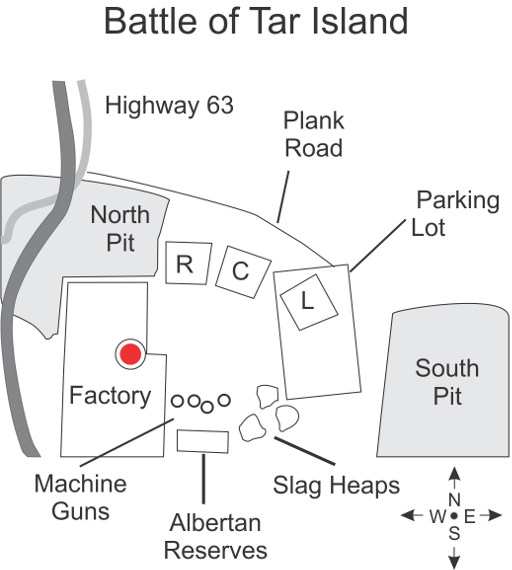

After less than a week they arrived at the tip of the North Pit, at the point where Lake McLellan, Highway 63 and the Athabasca River meet. They were one day’s march from the front.

Camping was arranged on an first come basis, except for the best spots, around Lake McLellan, which were reserved for the nobility and their horses. By the time Anton’s squadron arrived, the camp ground had spread out around the northern-eastern tip of the mine.

Because of the way the senior officers talked about the Tar Island mine, Anton had envisioned it to be like a flowering, stone garden. The terraced, muddy brown-grey North Pit might once have been an Eden for machines, but never one for humans.

The ground was wrinkled, sharp and hard. It had rained recently. There were dark pools everywhere that looked more like oil than water. Anton imagined that if he lit a match the landscape would burn like brimstone.

While they were setting up camp Anton stumbled upon the remains of a team of slaves who had died trying to remove a cannon from where it had become stuck in a crevice of bitumen. The weight of the weapon had caused a piece of rock to crack. This created a small landslide, which had half-buried the cannon. The slaves had no gloves, so their hands were scarred and bloody. They had been shot in disgust, or despair, by an owner who couldn’t collect on his contract to deliver the gun to the front. After camp was set up, Anton’s men removed the corpses from under the ruined cannon, and buried them in gravel.

The North Pit was a cemetery for machines from the Digital Age. It contained giant backhoes, pile drivers and trucks. A few were decrepit, but a surprising number were not. Their camp clustered around the edges of a 10 metre high dump truck, at the top of a switchback road. When the truck had broken, two centuries ago, it had held 400 tons of rock. Over time, most of the rock had fallen out through rust-holes, causing the truck to bury itself. Although it was a good site for camping because it was well-drained, flat and sheltered, it was a poor choice for the soldiers because the skeleton machine haunted their dreams. It was like sleeping on Grendel’s lap. §

The next day the Second Army began the last leg of its march, serenaded by the loudly cawing birds that nested on the walls of the mine.

Just south of Fort MacKay, on the northern edge of the Alaskan trenches, there was a bottleneck created by a plank road that had been placed directly in the path of the Second Army. Passage over the road was blocked by Alaskan MPs with drawn guns.

At first Anton could not determine why the plank road was there at all. Then he heard the clatter of hooves on wood. Slaves had built the road so that the Alaskan horsemen could reach their position on the Army’s left flank without having to risk crossing the hard, rocky ground.4

Although the plank road was barely 2 kilometres long, the progress of the cavalry from Highway 63 to its destination – the parking lot that traced the eastern perimeter of the factory – was slow. Every few minutes a horse would stumble and fall off the road. Most of those that did broke limbs and had to be killed.

The crowd of soldiers in the front end of the bottleneck became angry as they became more compressed. Conscripts started to heckle the cavalry. Phrases like “look at the pretty officers” flew through the air. The officers mostly ignored the jibes: they were too concerned about the safety of their mounts. It was the military police who took issue with the hooliganism.

Initially the MP presence was slight, perhaps one policeman every twenty metres. After an hour the entire length of the plank road was lined with police. They lowered their face masks. A few cocked their guns. Most were holding truncheons in their dominant hands, facing the crowd, waiting to be attacked or to attack.

One rowdy conscript fired his pistol into the air. A squadron of military police immediately pushed out into the crowd. The first to arrive shot the conscript. While this was happening the crowd unsuccessfully tried to edge away from the military police.

Once all of the cavalry had reached the parking lot, a checkpoint was opened in the plank road. All of the infantry slowly funneled through this narrow gap. The identity of each soldier was checked against a list.

It was dusk by the time Anton made it to the other side of the plank road. He was herded past the slave quarters to the portion of campground reserved for Shevetz’s Company.

Once his tent was set up, Anton left his men under the guard of his Platoon Sergeant, an Inuit from the eastern arctic who had the unlikely name McAllister. He set off for the trenches to see if his gun had arrived.

The trenches were numbered with an alphanumeric system. Anton followed a radial trench numbered 3 to where it intersected with row c. He found his gun in position, exactly as planned. He identified it as his by the crack on its muzzle.

A full moon had risen in the south-east, so Anton could see the battlefield clearly. His primary objective, the factory, was to his right – the south-west. The factory’s northern tip was behind Alaskan lines. That was very good news. The bad news was the row of machine gun towers to the south. They were close enough that Anton could see the face of the Albertan who manned the tower due south of him. The Albertan waved. He was wearing the Albertan version of the Bands, so looked like a glow-in-the-dark skeleton when he did so. Anton flashed the Albertan a peace sign with his right hand. The Albertan gave him a thumbs up.

To the east of the the Albertan machine guns was a field of barbed wire that ended in three slag heaps. Beyond the slag heaps, just north of the South Pit, was the parking lot where the Alaskan cavalry was camping. The cavalry camp looked like something out of Camelot. The officers had grand, striped tents. Even the horses had colourful temporary stables . The flickering light of hundreds of torches added to the sense of medieval pageantry.

The spectacle disturbed him as much as did the thin, utilitarian machine gun towers.

Anton crawled through the trenches back to the camp in a sombre mood. When he reached the point where the trenches and campground met a voice whispered out of the darkness, “My friend, what are you doing wearing your Bands? Do you want to get shot?” Anton looked for the source of the voice but couldn’t locate it in the blackness. He acknowledged the comment by waving his right hand in the approximate direction from which the voice had come, and then quickly slipped away to the privacy, and security, of his tent.

It started to rain.

For most of the night the rain fell as mist. §

The next day began with a court martial. A Sergeant had allowed the men he commanded to desert. They had escaped into the North Pit. The Sergeant’s trial was brief, just a bland recitation of the facts, and a sentence. The only part of the event that was contentious was the manner of execution, which was debated in loud, but unclear, voices by the court’s two presiding officers. In the end, the defendant was shot in the pen where slaves were flogged.

Anton planned to spend the day exploring the factory. Just after noon, he was informed that he had permission to do so. He left his men under the guard of one of the Colonel’s men – a noble from Fairbanks.